As you may have heard, the UK government wants to radically transform planning in England. Recently, to much fanfare on Twitter, the Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government (MHCLG) released a consultation on proposals for how exactly the government plans to do so.

The proposals contained in the consultation and accompanying White Paper will have a profound impact on the way that planning and development is prepared and delivered in England, but also in the way the public interact with the system. Community engagement is mentioned over and over.

Here’s what this could mean for democracy and the built environment.

(NB: This isn’t a political take; it focusses exclusively on the democratic aspects of the White Paper.)

What’s good?

There’s a lot to like about this in terms of tech and democracy. (I actually raised a lot of these issues in my response to Connected Places Catapult’s report on the future of Plantech. It’s almost like the government actually read my article. Surely not. Unless…?)

There is a strong theme throughout about harnessing digital technology to modernise the UK planning system. It’s been well documented that planning software is ridiculously inefficient, and its many issues could largely be solved by implementing the use of geospatial data rather than relying on paper or PDF documents.

Considering that Delib has been fighting the ‘data not documents’ battle for nearly 20 years now, it feels like a win when central government has come round to the idea.

“We are moving away from notices on lampposts to an interactive and accessible map-based online system – placing planning at the fingertips of people. Communities will be reconnected to a planning process that is supposed to serve them, with residents more engaged over what happens in their areas.”

Having a more visual and map-based consultation protocol just makes sense. Currently, you’re often expected to read through dense documents in order to be able to comment on a planning application. The White Paper acknowledges this ‘excludes residents who don’t have time to contribute to the lengthy and complex planning process,’ not to mention you basically need a lawyer to translate some of those documents.

Visualising what a development would look like in relation to its surroundings, rather than listing co-ordinates and describing features with jargon, enables residents to give more informed and considered feedback, while lifting the barriers to entry for most.

“It will be essential that [design codes and guides] are prepared with effective inputs from the local community, considering evidence of what is popular and characteristic in the local area….Designs and codes should only be given weight in the planning process if [local authorities] can demonstrate that this input has been secured.”

The public feel like they have virtually no control over what developments go up around them, so if done effectively this will foster a real sense of community ownership.

A beautiful, digital, data-driven and dynamic consultation process is truly the way forward. It opens planning right up to everybody, not just NIMBYists and stakeholders.

What’s less good?

There’s a LOT of talk about speeding up the planning process. Local plans should be delivered in 30 months, rather than several years; there’ll be deadlines for completing developments; local authorities to commit to building a certain number of homes or risk facing sanctions. But consider what we know about local authorities: most planning permissions are granted anyway; a council can’t actually control the speed of a development (and developers have been known to sit on land); and of course, council budgets are in tatters.

What then risks happening is developments which are rushed through as quickly as possible with insufficient time to get the community involved. If local authorities are focussed on building as many homes as they can, as quickly as they can, in order to avoid sanctions, will they realistically have the time or resource to consult properly? And if the public opposes a decision, will the local authority in question really be equipped to overturn it if they’re behind target?

Getting people involved in shaping the design codes in their city is a great idea. But that shouldn’t mean the end of planning consultation for the entirety of a Local Plan duration. Public involvement needs to be continuous in order for it to be democratic and accountable.

Oven-ready

As I mentioned, Delib has been fighting many of the battles mentioned in the White Paper since the dawn of time (2001). All of our tools are modelled on the premise that consultation and engagement should be digital by default, with no barriers to entry like massive documents, inaccessible language or needless logins.

Citizen Space is ideal for running planning consultations: features like response publishing, integrated feedback and simple, intuitive analysis tools all make the process simple and effective for both citizens and planners.

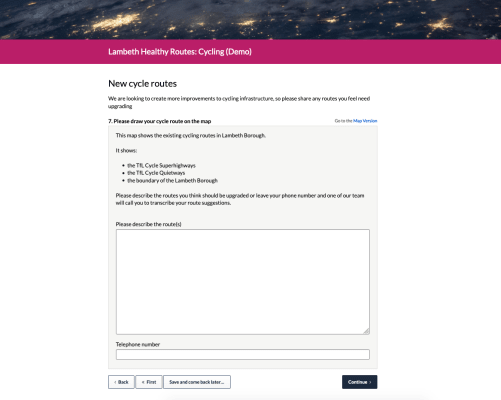

We also offer a dedicated geospatial capability which can be added to a Citizen Space subscription: Citizen Space Geospatial. It allows users to include maps and geospatial data throughout their consultation and engagement processes, enabling them to gather richer, more insightful data than ever before. Find out more about it.

This is good news, because it means organisations don’t need to wait until the government writes these reforms into law to make beautiful, accessible planning consultations. Read about how, by using Citizen Space, Hamilton City Council (NZ) cut the consultation process time of a Local Plan down by a whole month, even though they received 10x the previous amount of responses.

So all in all…

It seems as though the government is aware of the pattern of distrust and disappointment in the planning system from the public’s point of view – read more on this here – and understands that the road towards rebuilding (pun intended) involves, well, involving people.

What concerns me is that there doesn’t seem to be much consideration of how the consultation process actually works. There’s so much focus on speeding up the planning process that time and space for local authorities to consult properly hasn’t really been factored in. For local communities to actually co-produce these design guides and shape the future of their cities, towns and countryside in meaningful ways, you need to allow the time and resources for multiple consultation stages and a real, concerted effort to reach all demographics of an area.

(It’s also difficult to escape the irony of the fact that, although the paper waxes lyrical about the need for data not documents, and accessible, visually descriptive consultations, the consultation itself was only initially accepting responses via email.)

Introducing place-based engagement with Citizen Space Geospatial

Include maps and geospatial data throughout your consultation and engagement activities.

Find out more about Citizen Space Geospatial.

We’re confident that Citizen Space Geospatial solves a lot of problems for a lot of people. But who defines those problems and how specifically do you solve them?

Citizen Space Geospatial was designed based on user research involving over 20 government organisations. You can read about the user research journey here.

How did we go about building Citizen Space Geospatial? What were the challenges? You can read about the engineering journey here.

How can geospatial tools include people who, for whichever reason, can’t use a map? Read about how we designed for accessibility and inclusion.

What is geospatial data? Why is it important for democracy, consultation and engagement activities? Read a detailed overview.

To find out more about Citizen Space Geospatial book a demo and we’ll walk you through it.