Software used today by public sector urban planners is a jumble of proprietary tools that complicate tasks and reduce productivity. New tools have started to emerge in an attempt to break this mould and the entire planning software sector is ripe for innovation.

Recently, Connected Places Catapult released a report called ‘Transforming the digital architecture of planning: A critique of planning software today and the pathway to a more open, innovative and interoperable planning software landscape’.

Reading through it, I was transported back in time to my tenure working at a local council, where in order to apply for a simple paid service, a user has to download or print a form, fill it in, post or email it back to the council, where an officer then inputs the data into an internal online form, prints out the form if it came in by email, writes the order number on the paper form, scans it, uploads it, and emails it to Accounts who then invoice the customer. Then, if the customer hasn’t provided an email address, the officer prints out a letter confirming their order number, writes out an envelope, and posts it. And THEN the customer has to wait a month for their service to start. (None of this is an exaggeration.)

Planning, for the most part, currently occupies this space of inefficient and convoluted council processes. Granted, my example above could so maddeningly easily be solved by a simple online form (to date, it has not), whereas planning relies on maps, which are inherently a bit more complicated than a simple name and address. Catapult details how planners rely on a back office software market that is mostly dominated by two companies, both of whom offer what are essentially document management systems; but due to the different processes at different councils, these solutions often have to be shoehorned into place with frequent need for cheats and workarounds depending on the setup.

One of the really remarkable things about the planning system as it currently operates is that the bulk of the software on which it relies is pretty much incompatible with geospatial data, or GIS applications. It really is baffling that computer systems that are designed specifically for planners – whose job it is to work at computers and deal with place-based data – haven’t factored in the existence of computerised place-based data into their design.

As Catapult puts it, ‘the relationship between GIS mapping and planning systems is an exemplar of what could be termed a Tragedy of Interoperability.’

And that kind of sums up what’s highlighted in this report: planning software, despite being used exclusively on computers, barely functions on computers.

‘Using today’s planning software presents a constant battle between learning the software, creating workarounds for limitations in the software, formatting documents to export, and then importing back into the software. All of which consume huge amounts of time that should be devoted to the actual practice of urban planning.’

One thing the report doesn’t delve into in enough detail is how this ‘monolithic software affliction’ affects not just planning officers but the public too. Ordinary people need to be able to interact with this confusing, opaque system because we, as citizens, should be able to influence decisions that will permanently affect our cities, villages, homes and landscapes.

Firstly, it is not an easy process to send in a planning application. Usually it involves sending five or more discrete documents, either through the post or via the central-government owned Planning Portal, which is a job to navigate in itself. It can also be difficult to find and comment on an existing application; in many cases it’s practically impossible unless you have a direct link. Not to mention that, due to issues surrounding redaction and GDPR, some councils end up electing not to publish planning representations altogether, because their document-based process means that time-stretched officers are receiving representations, then having to print them off, redact them with a sticker or a Sharpie, scan them back in and re-upload them.

Then add to this that many planning consultations are difficult to access or require a respondent to download heavy technical documents and it’s little wonder that the planning process is roundly viewed by the public as undemocratic and unaccountable.

So what do we do about it?

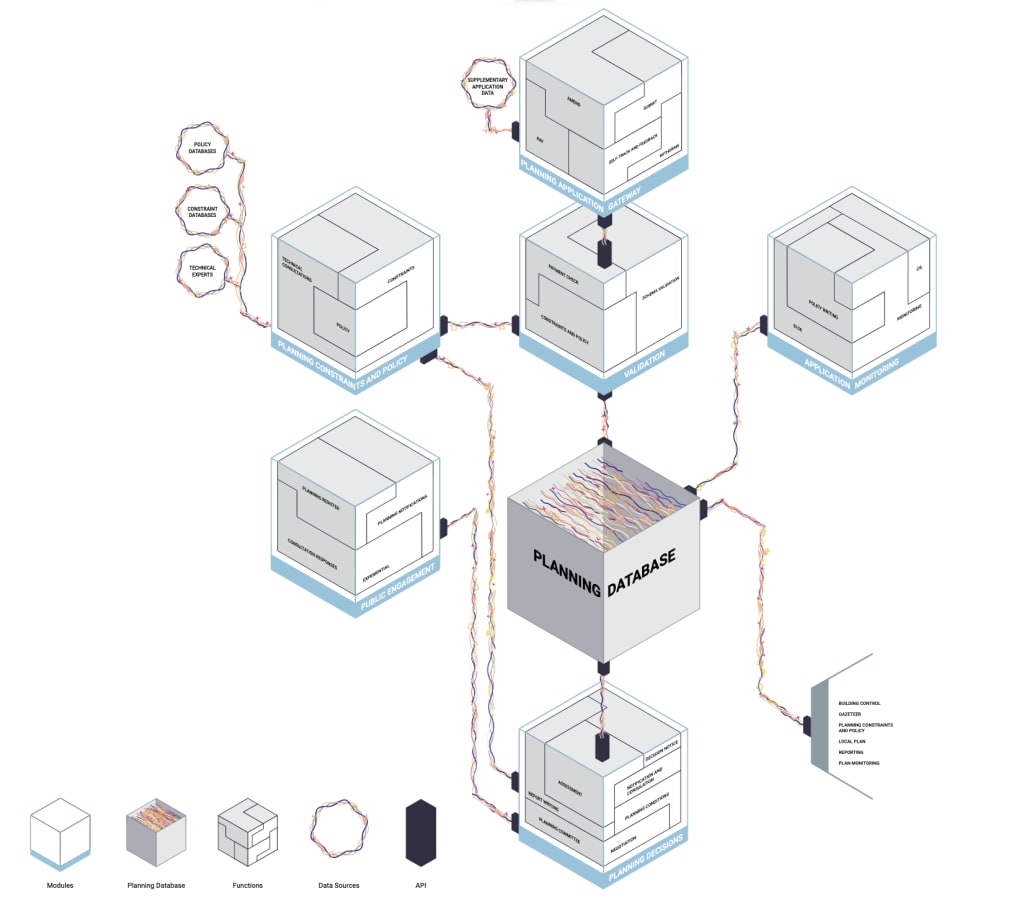

Catapult argue for a planning system that’s serviced by a modular software system, with different interconnected solutions all working from the same API (or, if you’re like me and don’t know what an API is, an interface that lets software interact with other software) and therefore all able to communicate with each other. Broadly this sits in line with Delib’s principles; we offer discrete tools rather than an ‘all-in-one engagement suite’. An organisation should have the option of deciding which tool is best suited to the activity they are running, rather than trying to mould it to fit a piece of software they happen to have.

That being said, the #plantech revolution won’t get far if these ‘modules’ are too fragmented and all of a sudden councils find themselves having to procure/navigate eight different bits of software just so they can do their day-to-day jobs. The planning industry doesn’t need blingy, shiny tech that incorporates VR or AI right now – it needs to focus on fixing the plumbing first. Not to mention cultural barriers: if paper- and document-based systems can persist in almost all UK planning departments in 2020 and beyond, any alternative will need to be uncomplicated and demonstrably cost-effective to stand a chance at penetrating the market.

For planning to become truly efficient, effective and democratic, it needs simple, comprehensive tech platforms that incorporate the best of the rich, open geospatial data that’s out there – and sack off documents once and for all.

Update 4th Feb 2021: Delib launches new #PlanTech product

On 04/02/2021, Delib launched a new product: Citizen Space Geospatial. It is now available for users around the world to conduct place-based consultation and engagement processes.

Citizen Space Geospatial allows users to include maps and geospatial data throughout their consultation and engagement processes, enabling them to gather richer, more insightful data than ever before, solving many of the problems of interoperability raised in this article.